“I hate my teacher,” *Elora, 9, declared to her mother. But, when pressed for details, her mom says Elora buried her head in her knees. So she tried a different approach. “I engaged her in a fun activity,” she says. “Then I lightheartedly asked questions like who she likes the most at school, who she likes the least, followed by, ‘oh, how come?’ What I found out was that ... she felt like the teacher yelled at her.”

Why the grumbling? An elementary school child’s disdain for her teacher may grow out of a variety of factors, like adjusting from a beloved former teacher’s management style to a new teacher’s approach. Other influences on a child’s attitude toward his teacher include class size, peer competition, increased homework, more demanding, independent school work, as well as differences between home and school environments.

Do some digging. Allow your child time to adjust to her teacher’s expectations and rules. If her complaints persist, ask objective questions, like: “How is the work for you? How are you getting along with the other kids?”

“By doing that you can get a flavor of the environment rather than the situation,” says Dr. Stephanie Mihalas, a child psychologist and a nationally certified school psychologist, who frequently helps students and parents manage and resolve school conflicts. “You may get an idea that something else is happening that’s triggering the ‘meanness’ and then at that point, you have more information to call or email the teacher.”

Review class work. Notice patterns like notes from the teacher and red marks on classwork. If your student struggles and seems afraid to ask questions, discuss appropriate times for her to talk to her teacher about the work and what types of questions she should ask.

Make real-world connections. A child may grow disenchanted with school and her teacher if she doesn’t understand how the subject matter relates to real life. Due to increased pressure to focus on testing and assessments, teachers devote less classroom time for experiential learning opportunities or class projects.

That’s where a parent can help.

“Engaging in the learning piece is key,” says Ashley Norris, Ph.D., assistant dean, University of Phoenix College of Education.

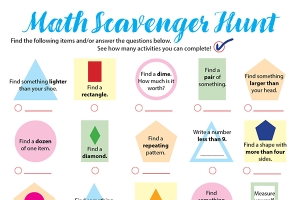

On the weekends, integrate classwork into your daily errands. For example, if your child is learning about the soil and the climate in science, take him to the Saturday morning farmer’s market. Practice multiplication skills to tally up the tip at a restaurant.

“Parents (then) become a partner with the teacher. Once that engagement starts to happen, the perception of the student-teacher relationship changes,” Norris says.

Signs of a child-teacher conflict. “The single biggest factor is a change in grades. If grades are starting to slip, that’s a huge indicator,” Norris says. Behavior changes can also indicate a problem, including disengagement at school, forgetting homework and lack of effort.

Resolving a personality conflict. Rather than getting angry or defensive, take a calm, diplomatic approach when conferencing with the teacher.

“The last thing you want to do is instigate more conflict between the teacher and your child and if you start to pit sides, that’s what ends up happening,” Norris says.

Also, ask if you can sit in during class one day.

“Your presence might change the nature of how your child acts, but it will give you a flavor of how the teacher teaches,” Mihalas says.

When to contact administration. Go over a teacher’s head only as a last resort. “One of the only times to bring in administration is if your child is covered by special education law and the teacher isn’t following special ed law,” Mihalas says.

Other times you might seek help from administration:

The teacher agreed on a set of interventions, but isn’t following those strategies.

Your child comes home crying every day.

You talk with the teacher and are unable to resolve the issue.

Request a different teacher? Sometimes a child’s personality and a teacher’s personality simply clash. Unless the teacher is abusive, help your child understand that she’s not always going to like everyone, stressing the importance of remaining respectful and learning how to manage personality differences.

“In my humble opinion, I don’t think it’s a good idea to show children that because there’s a problem then they need to move from that classroom,” Mihalas says.

Instead teach flexibility by creating a link between friendships and getting along with others. For a younger child, you might say: “Everyone is different. Just as mommy and daddy do things differently, this is how your teacher is. It’s really good to learn how to work with all different kinds of people.”

Seek professional help. If interventions at school are unsuccessful, seek help from a child psychologist to rule out learning disabilities and anxiety.

Questions to ask the teacher:

Have you noticed my child struggling with a particular subject?

Does she participate in classroom discussions?

How does she seem to get along with her peers?

How can we work together to help my child better adjust?

----------------

Freelance journalist Christa Melnyk Hines is a family communication expert.

*Name changed.

Published: August 2013